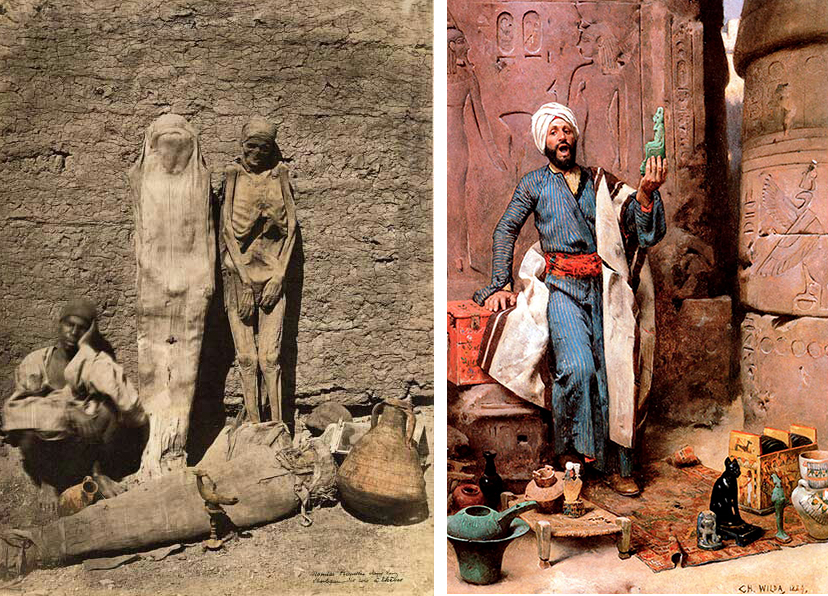

The Abydos archive team recently started work on an exciting collection of newly acquired documents from Tuna el-Gebel. Amongst the intriguing papers that we discovered during our initial sorting phase, were two large files labelled “Umbarak Basha Ahmed”. Upon closer examination of the more than 200 documents held in each file, we discovered that Umbarak was a rais from Qift that had been employed by the government in 1947 to work on their excavations. Initially we linked him to the rais Umbarak who had worked with the EES in the 1930’s at Amarna, but the dates didn’t match up. Born in 1913, Umbarak Basha Ahmed would have only been a teenager at the time, and not the ‘older Umbarak’ as described by Mary Chubb.

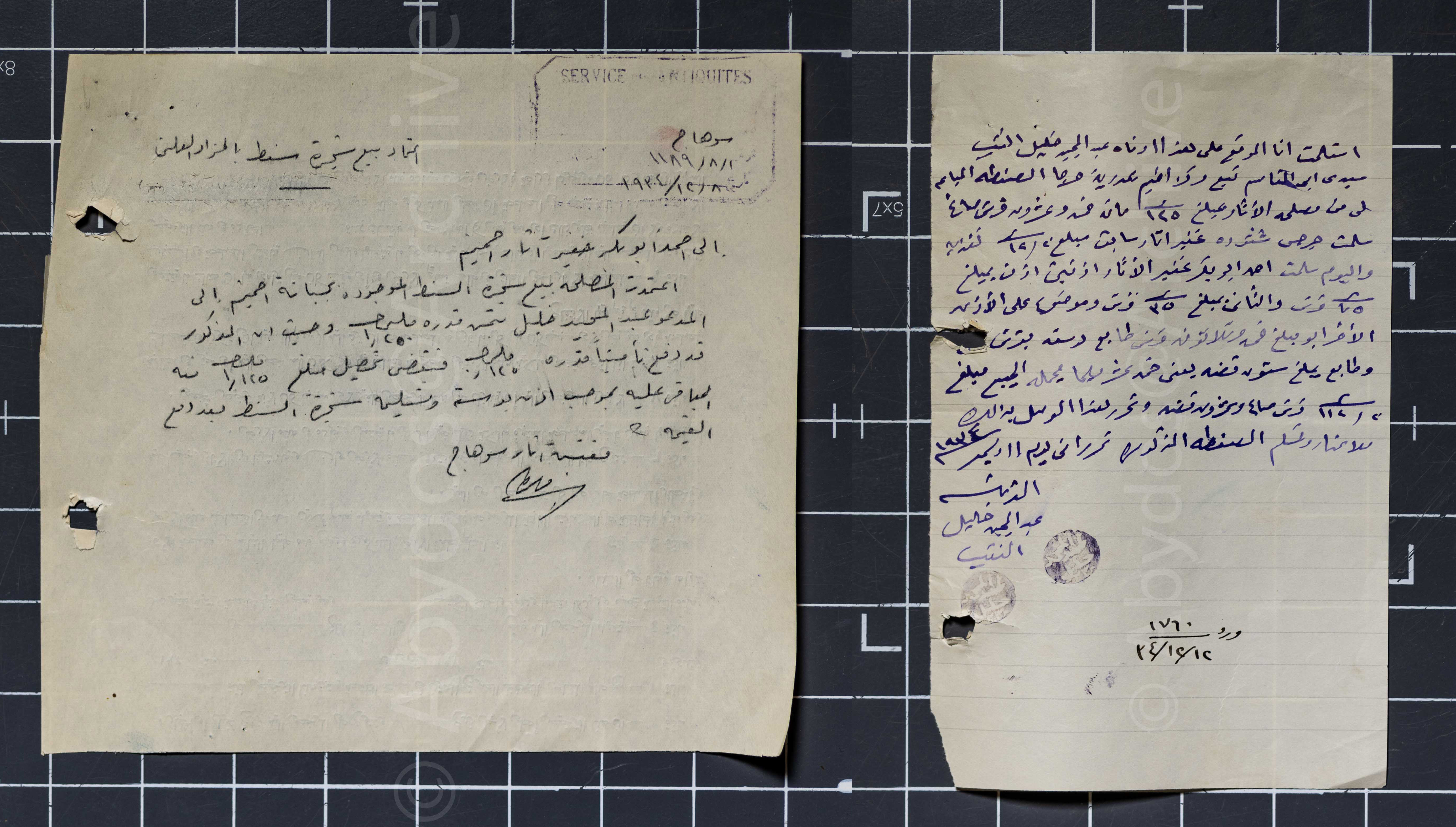

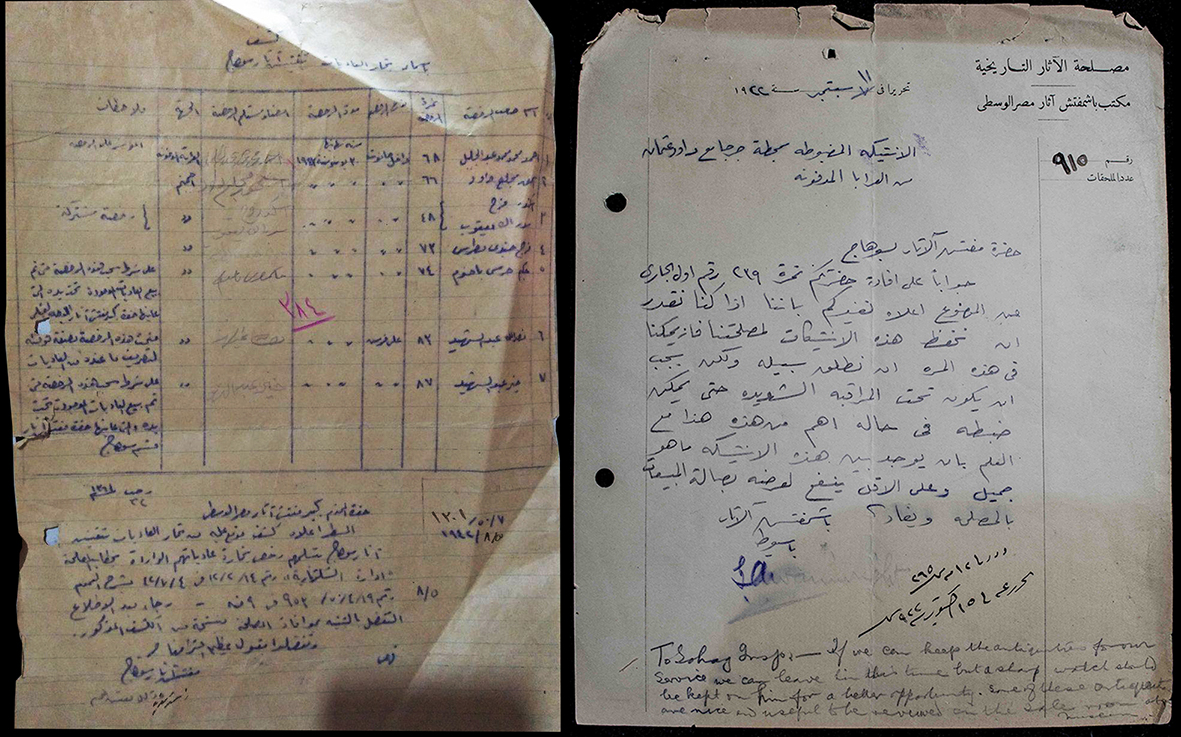

The file of Umbarak Basha Ahmed

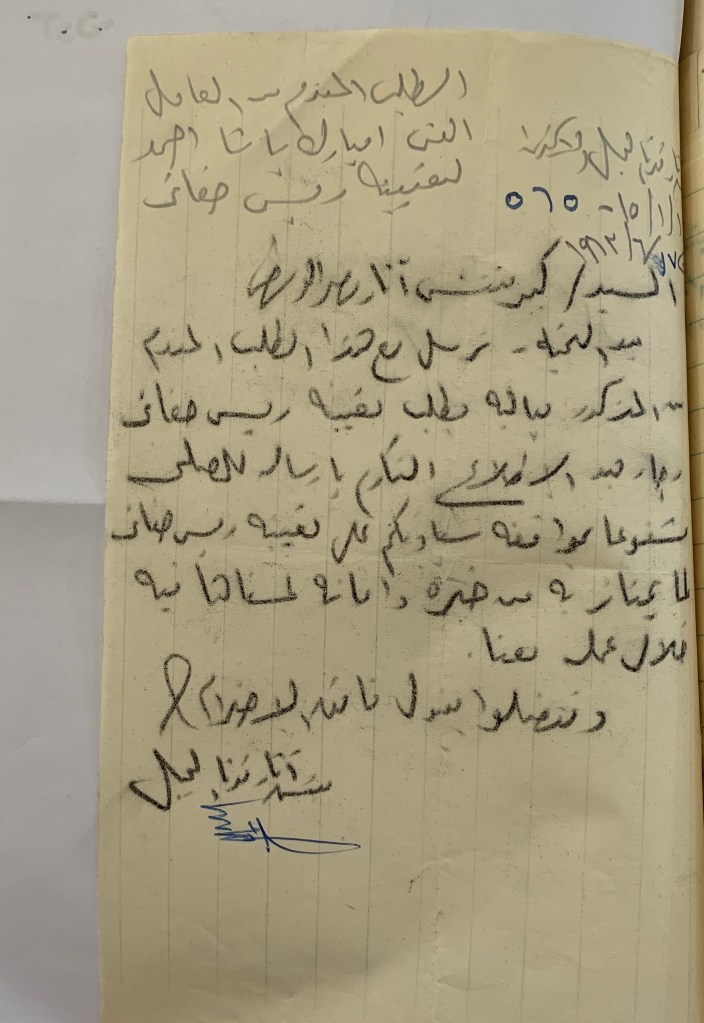

His file tells us that he started as a temporary ‘excavation technician’ or archaeologist with Cairo University in November 1946, and worked on their excavations at Tuna el-Gebel in 1959, before being transferred to the Inspectorate of Minya in May 1960. In 1963, he sent a request to the Antiquities Service asking to be promoted to a rais due to his excellent excavation experience – a request that was sadly denied as the Service claimed to have no vacant positions to offer. This, however, seems to have changed a few years later when his is referred to as a rais in all the correspondence.

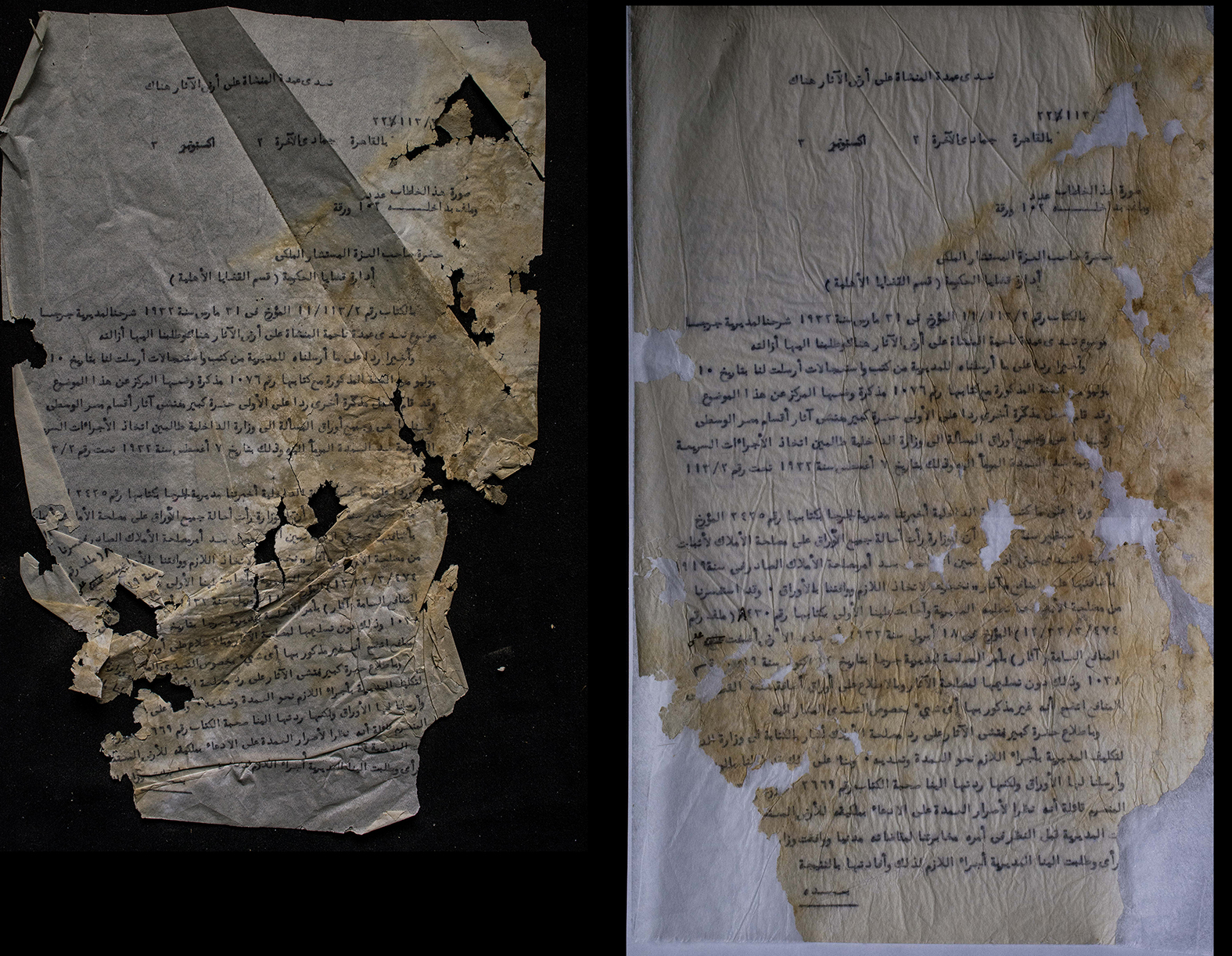

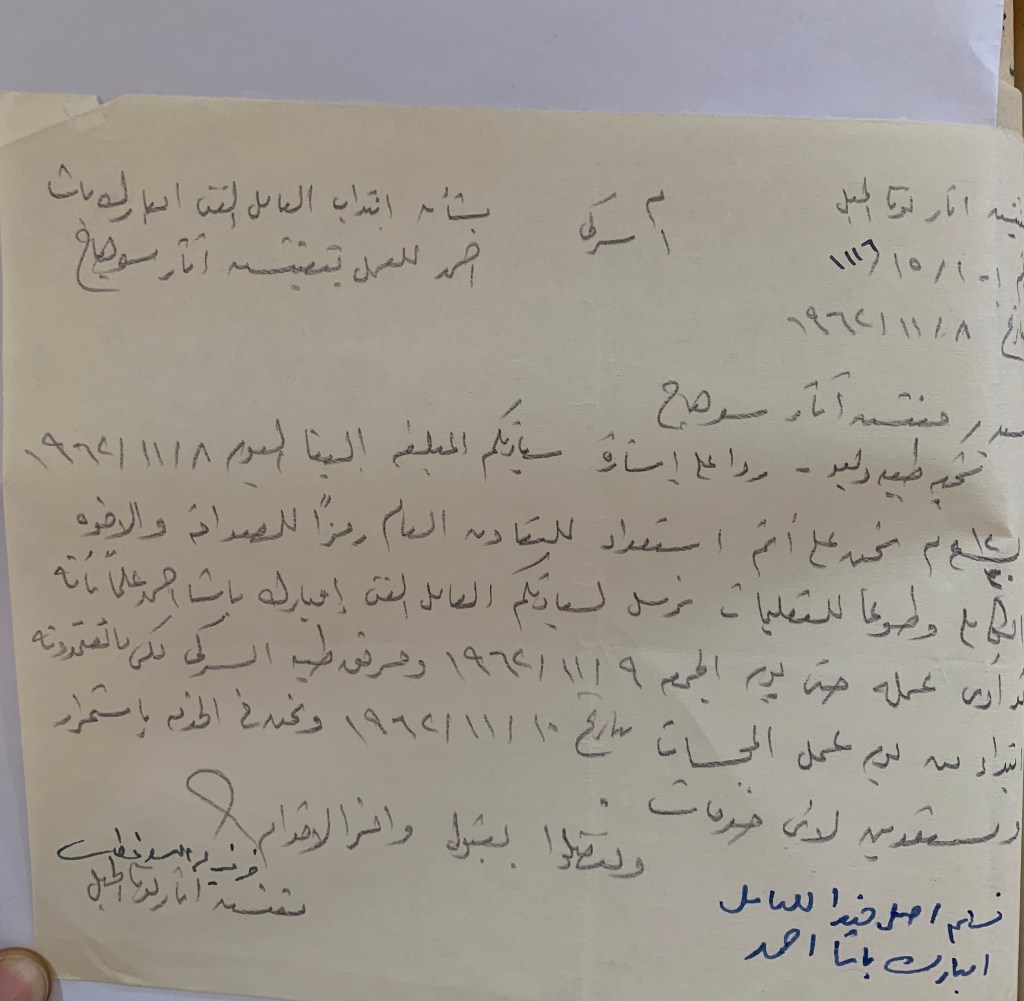

A request to promote Umbarak Basha to rais

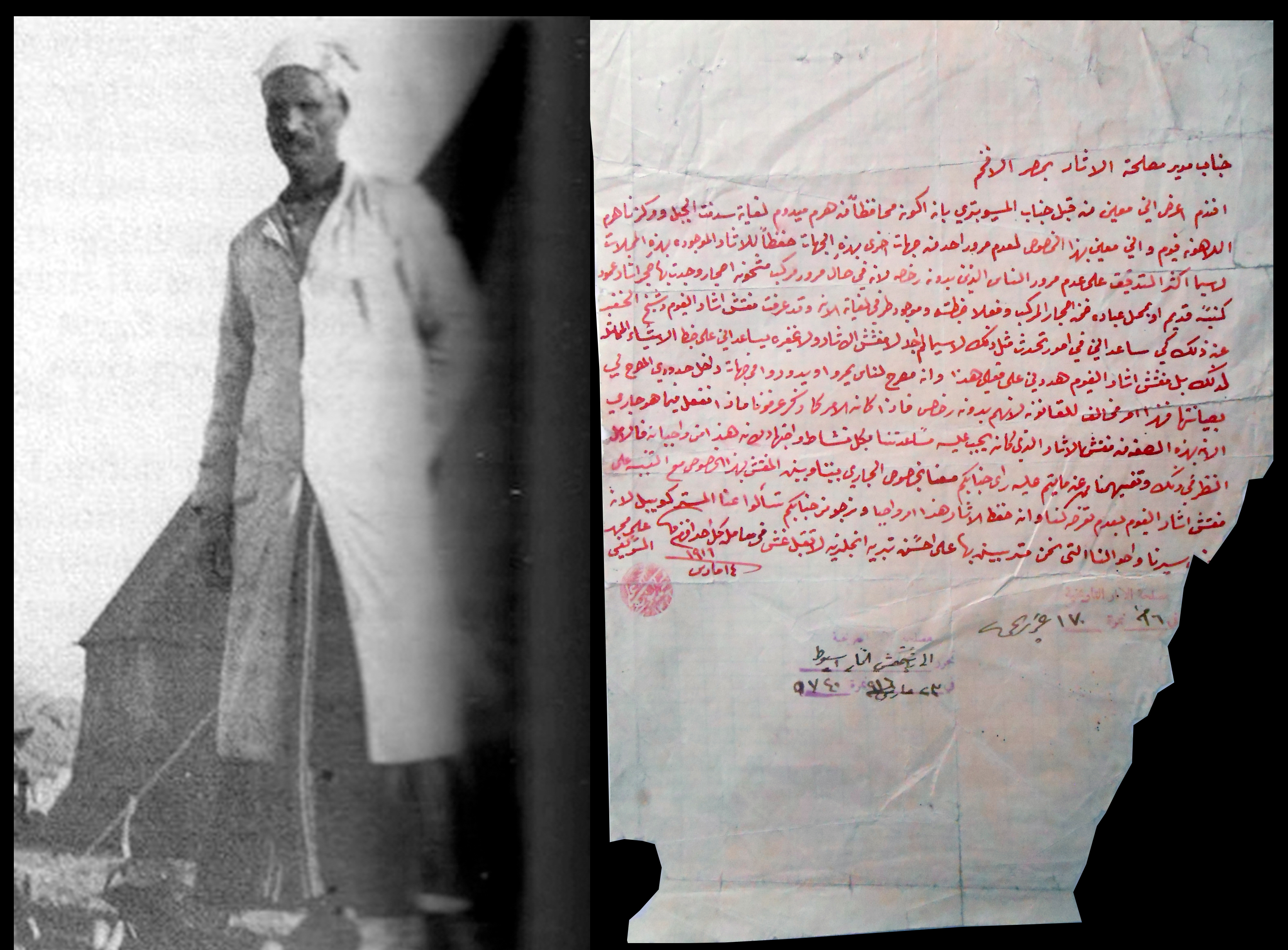

In 1962, the Tuna el-Gebel Inspectorate lent him to the Sohag Inspectorate to dig a series of test pits in Abu Tig, writing that they do this in ‘the spirit of cooperation and as a symbol of friendship and brotherhood’. In 1963 he joined Cairo University’s 4th season of excavation in Nubia, most likely as part of the UNESCO Nubia campaign, and later that year he was sent to work in Manqabad in Assiut.

The Tuna el-Gebel Inspectorate agrees to lend rais Umbarak to the Sohag Inspectorate

Sadly his career came to an abrupt end at the end of 1963 after he fell ill and was unable to work for 10 years, finally retiring in 1973. His doctor’s note claims that his illness was as a result of the dirt he was exposed to from years of clearing tombs.